2024 started with a wave of massive protests from farmers across Europe, who grapple with low incomes, a lack of future prospects, and the consequences of decades of unsustainable policies. We share their fight for a fairer agriculture system and for an end to agreements favouring corporate giants. We share their call for a genuine transformation of agricultural policies, placing peasants, small and medium-scale farmers at their forefront.

A new front in peasant struggles

Against the backdrop of increasing corporate control in agriculture, a new facet of peasant struggles for social justice, power balance and autonomy comes to light: digital farming. Why? Because the intrusion of Big Tech in agriculture risks deepening farmers’ dependency on corporations, potentially eroding peasant autonomy and knowledge.

On this International Day of Peasant Struggles, we want to emphasize the importance of protecting peasant intelligence and farming, crucial for sustainable food systems, and caution against portraying digital technology as a silver bullet.

Decoding digital farming

Digital farming, propelled by Big Agri and Big Tech corporations (like Bayer, Meta and Alphabet), is gaining traction globally. It involves using digital technology to observe, monitor and manage farming activities and other parts of the supply chain in an integrated manner, including mass data collection, storage and analysis.

Despite claims from policy makers, corporate interests and some researchers about the necessity of digitalising agriculture, critical attention must be paid to the economic interests behind digital farming solutions. From the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) to Automated Decision Making (ADM), many of these technologies are promoted as indispensable tools for innovation, when they actually often serve to consolidate corporate and political power rather than improving farmers’ livelihoods.

Preserving farmer autonomy in the face of Big Data

Peasant farmers already face highly concentrated markets for seeds, pesticides or fertilizers, and now a handful of corporations also seek to gain further control over farms through big data.

In all aspects of society, the aggregation of data allows it to be transformed into a valuable commodity. So it should not come as a surprise that Big Agri, Big Tech and financial institutions all find the emergence of big data in agriculture an attractive prospect. But big data services are being set up in a way that leads to farmers losing data ownership rights once aggregated, leaving corporations alone to reap the profits.

High tech vs low tech solutions

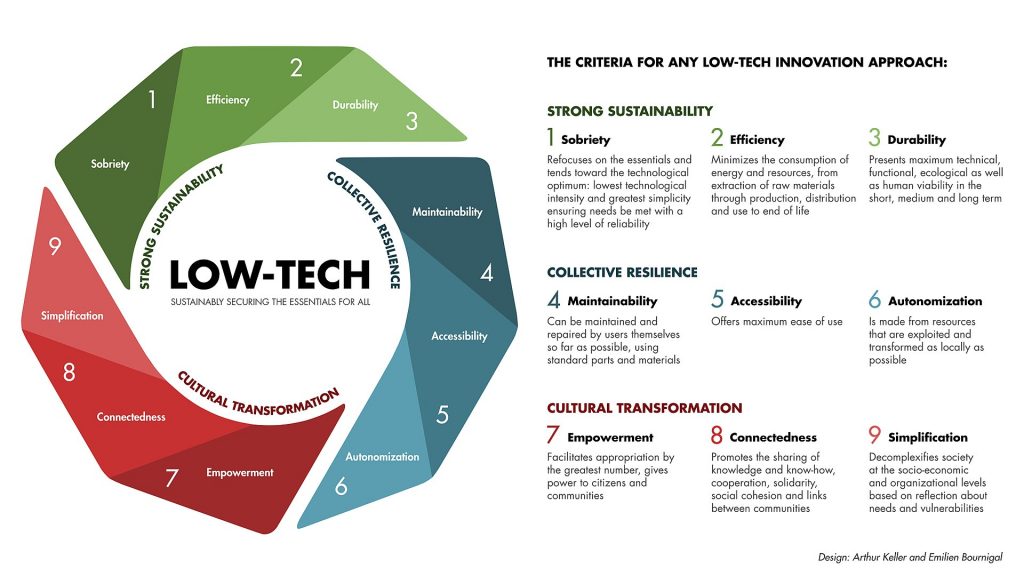

While high tech digitalisation dominates policy discussions, masking other valuable developments and forms of knowledge in the digital transformation, it’s essential to recognise the value of low tech solutions in farming.

Low tech refers to “ the design and development of products, services, processes or systems that aims to maximise their social utility, and whose environmental impact does not exceed local and planetary limits. […] The low-tech approach also allows as many people as possible access to the answers it produces and control over their content” (ADEME). This approach, controlled by local communities, often aligns better with the needs of peasant farmers.

That is probably why, despite the corporate push for the use of digital intelligence in farms, the reality is that many European farmers have a limited uptake of digital tools.

When corporate-driven digital farming create new monopolies that could bind farmers further, and even partly replace them with automated systems and digital machinery, low tech solutions centre on farmer-driven technologies, practices and knowledge.

Empowering farmers

Peasants should adopt digital tools when they directly benefit from them. Instead of promoting digital farming as a cure-all, we must acknowledge the extreme imbalanced bargaining power that can lock farmers into unfair contracts with corporate giants.

And before endorsing digital farming in public policies, policy-makers must ask themselves: What is the objective of data collection? Who is involved in the decision-making? Who designs the algorithms and on what assumptions are they based? And ultimately, who profits?

Technologies are not neutral; before embracing digital farming, we must guarantee data sovereignty for farmers. This means striking a balance between peasant knowledge and additional data to ensure that those who produce food retain control.

The slow uptake of digital tools and data collection in agriculture means peasant farmers, supported by civil society, can still steer towards an agriculture where they have the power to decide what’s happening in their fields, and with their farm animals. Not Big Agri, nor Big Tech.

Further reading:

- Friends of the Earth Europe’s Report on digital farming: From data giants to farmer power

- Friends of the Earth Europe, FIAN International and the Centre for Agroecology, Water and Resilience at Coventry University Report on Remote control and peasant intelligence

- SOMO’s Report on the financialisation of Big Tech

- Transnational Institute’s infographics on Big Tech and the rise of GAFAAMT

- Transnational Institute’s article explaining why digital capitalism is a mine not a cloud