After Donald Trump’s decision to pull the United States’ out of the Paris Climate Agreement, Europe and China stepped up the rhetoric to position themselves as global leaders on climate action. But with negotiations on the EU’s climate plan for 2030 underway, does the action meet these warm words? ask climate justice and energy campaigners Clémence Hutin and Molly Walsh.

—

The implications of the US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement

The Paris Accord, signed by 195 governments in 2015, signaled that governments of the world recognise the problem of climate change and aim to tackle it. The text falls short of what science and equity require – commitments are voluntary, they lead us to +3°Celsius of average global temperature rise, and it undermines the principles of climate justice. Nevertheless, the US withdrawal from the deal is deeply significant.

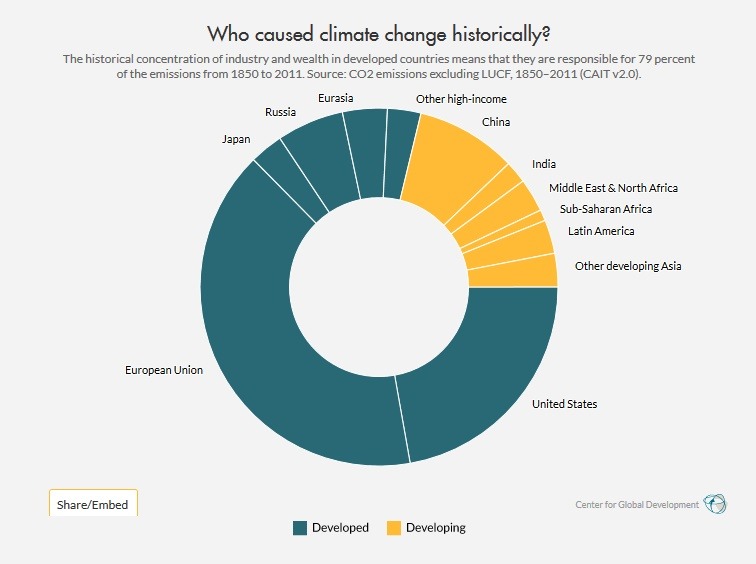

The United States is the second biggest polluter globally. According to the Fair Shares analysis, the country needs to achieve a 65% reduction in emissions by 2025 (compared to 1990 levels): this is more than five times the country’s current climate action.

By withdrawing, Trump is not only ruining tremendous diplomatic efforts, so crucial in the face of a global crisis, he is also sending a clear message he has no intention of seriously acting on climate. Trump’s close ties to the fossil fuel industry, and his choice for cabinet members, offer little hope of a reversal on his position.

After the announcement of the withdrawal, decision-makers were quick to step up and claim the decision would only strengthen their resolve. To quote Miguel Arias Cañete, EU Climate and Energy Commissioner, “[This] decision has galvanised us rather than weakened us.” A closer look however, reveals progress is still stalling in Brussels.

2020: a closing window for EU action

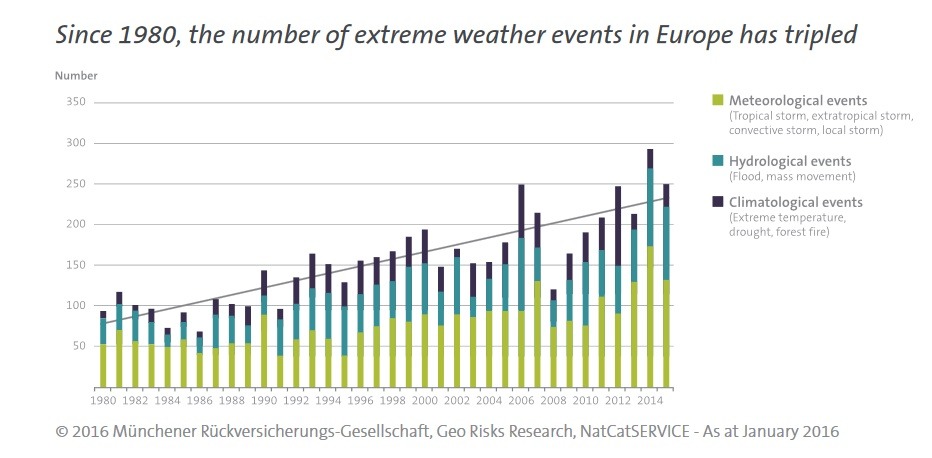

The 2020 climate package required a 20% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2020 – but science and equity call for double that effort. Climate change doesn’t negotiate, and the clock is ticking. The number of extreme weather events in Europe has tripled since 1980, and new figures show we could pass the critical 1.5°C increase of average temperature, which the Paris agreement aspires to stay ‘well below’, within ten years.

Owing to an economic crisis and the outsourcing of our emissions, the EU has achieved its climate targets early – but instead of ramping up ambition, policy-makers are resting on their laurels and delaying crucial action that should have taken place yesterday, demonstrating a clear lack of political will.

2030: a new chance to scale up targets

The Paris Agreement has the merit of reopening a discussion on climate objectives in the EU. In November 2016, the European Commission published a new ‘Winter Package’ of legislative proposals to increase climate objectives for 2030 in accordance with the deal. Among the files being reopened, energy efficiency and renewable energy: the two sides of the transition coin to a safe energy future.

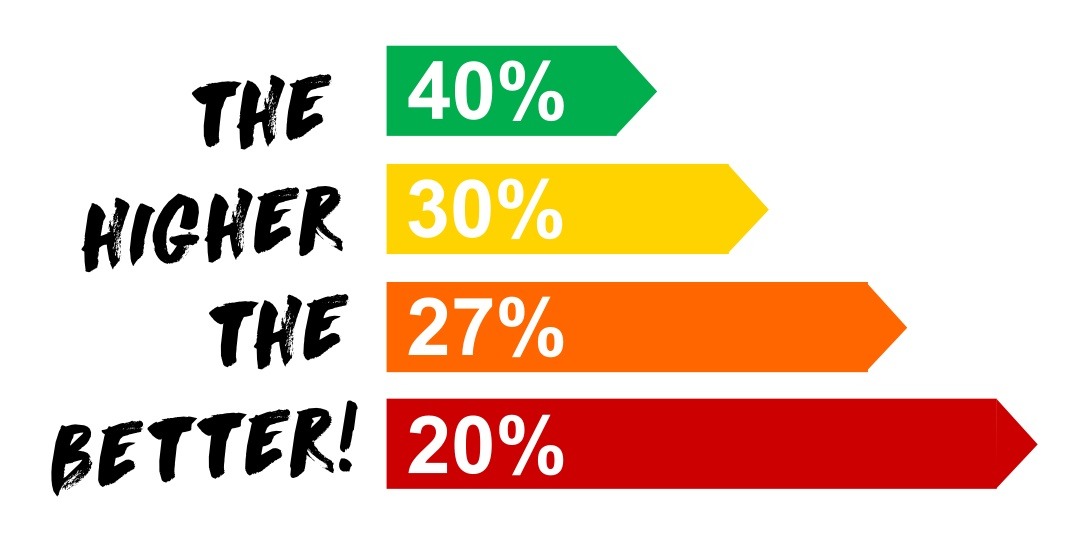

Dark clouds are looming over the energy efficiency target

The cheapest, cleanest and safest energy is the one we do not use: according to the International Energy Agency, the majority of greenhouse gas emission cuts in the EU must come from a more efficient use of our energy. Despite this, member states are negotiating a weak efficiency target – the 30% proposal from the European Commission, when much more is possible. Furthermore, the European Parliament’s support for a 40% target is now at risk, which could scrap all chances of achieving an adequate objective in ensuing negotiations with EU governments. This is despite the Commission’s own research showing 40% is within reach and would multiply the benefits of energy efficiency: energy independence, fighting energy poverty,, local green jobs, reduced gas imports and stopping new fossil infrastructure.

Mixed messages to support renewable, community-owned energy

On renewables, governments are also resisting a higher target. We know it is crucial for energy to be in citizens’ hands. People are best equipped to evaluate their own energy needs, and when people own their energy, they also reduce their need for it. There is general acceptance that we need to be 90-95% powered by renewables by 2050: setting a target of less than one third by 2030 amounts to planning to fail. Additionally, technicalities in the legislation known as “capacity mechanisms” would continue to support fossil fuel infrastructure: these payments are set to keep outdated and polluting power stations on the grid, in essence, providing life support for dirty energy infrastructure. This at a time when we have overcapacity in the energy market and need to be actively planning to get fossil fuels off the system, not subsidise for decades to come.

When the Paris Agreement was signed, our position as an international grassroots network was clear: a commitment on paper will not bring about the deep changes we need in our energy system. We need action not words. If the EU seeks to be seen as a climate leader, its 2030 climate plan is the chance to demonstrate it is worthy of this title.