In this blog for GreenWorld, climate justice and energy campaigner Clémence Hutin writes about the significance of Europe’s heatwave of 2018, and how it should be a wakeup call not for a #fossilfree Europe and for tackling summer energy poverty.

Killer heatwave

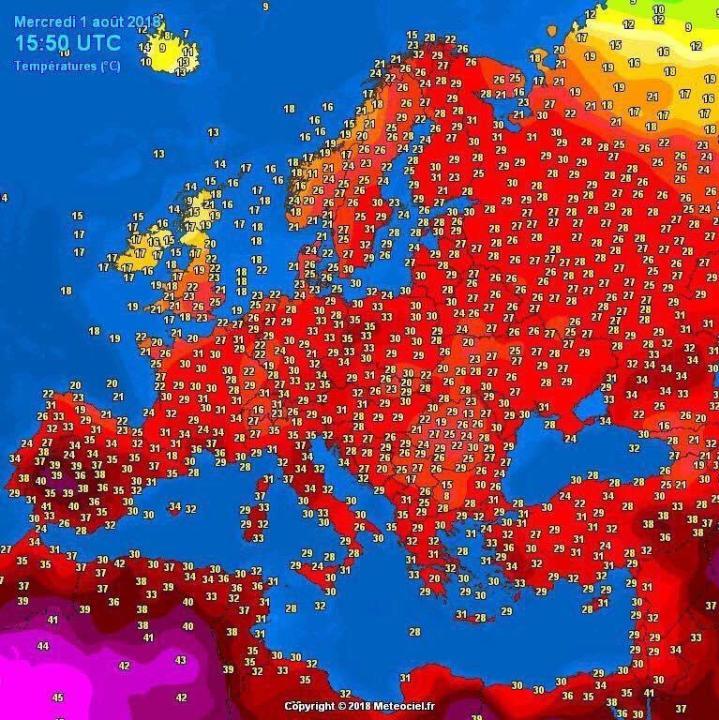

No-one this summer can have failed to notice that the world is on fire. Satellite pictures show us a brown, parched continent. People are feeling the heat of climate change.

This must spur deeper, transformational climate action across Europe. But with the chances of another such heatwave put at once every five years (according to current rates of global warming), action must also include helping people to adapt and withstand the impacts.

The World Meteorological Organisation already ranks 2018 as ‘one of the hottest years on record’, following a worrying streak of broken records in 2016, 2015 and 2017. This year, the UK experienced its hottest June ever, while forest fires raged in the Arctic Circle during Sweden’s hottest July in 260 years, and in the surrounds of Athens, at least 90 died in similarly devastating forest fires.

Thanks to ever-improving scientific research, we can now more confidently state the influence of climate change on extreme weather events: it made this heatwave twice as likely to occur.

But one overlooked question all this heat raises is what this means for those living in energy poverty, unable to cool their homes in summer?

Just had a chance to take my first photos of dried-out Central Europe and Germany since a few weeks, and was shocked. What should have been green, is now all brown. Never seen it like this before. #Horizons pic.twitter.com/o2XoddPdrM

— Alexander Gerst (@Astro_Alex) August 6, 2018

Understanding summer energy poverty

When we think of energy poverty, we usually think of freezing pensioners in winter unable to heat their homes. But energy poverty also causes harm in summer.

Extreme summer heat poses a public health challenge. Heatwaves already kill 12,000 people every year around the world. These past weeks, record numbers of people were admitted to hospital in the UK, overloading already stretched staff and resources. In Japan, more than 130 people have died and 70,000 rushed to hospitals, while in Quebec, the heat claimed the lives of 90.

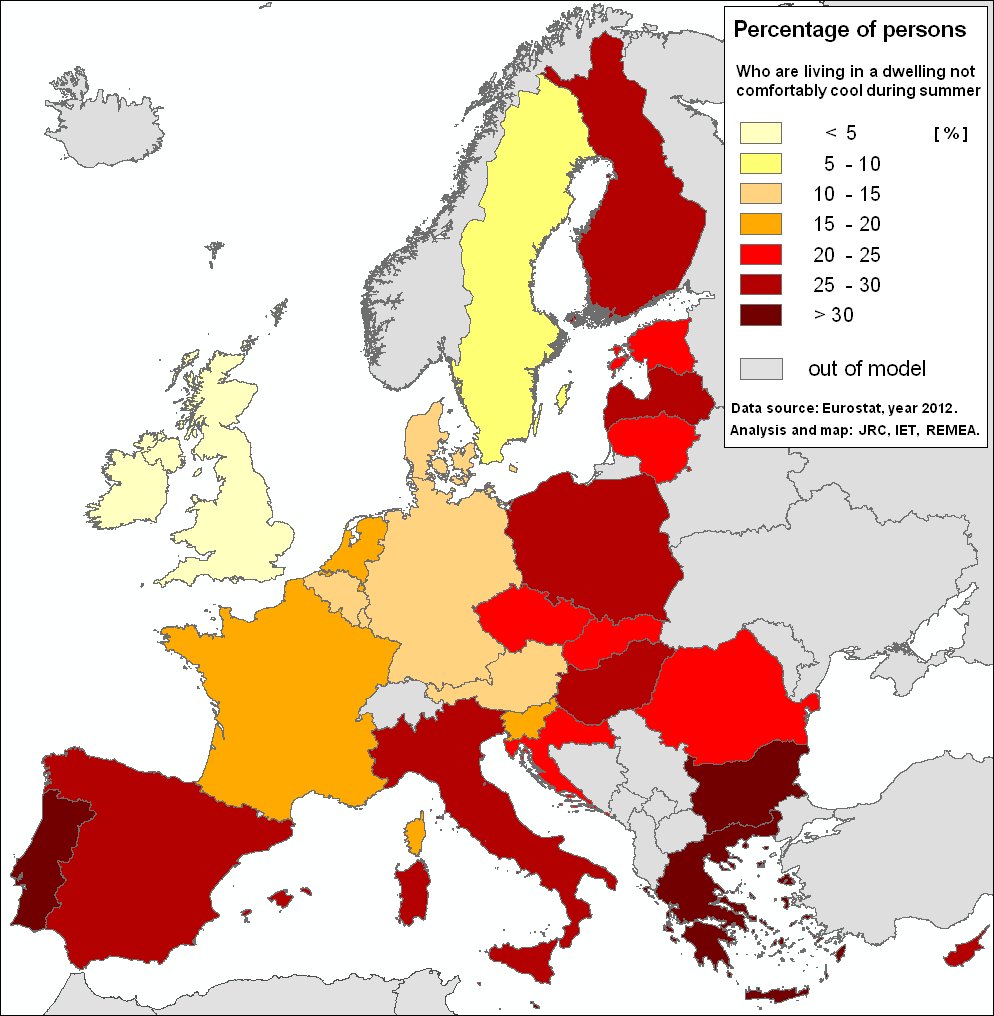

But this is not solely a problem of heat – it is also a problem of poverty and inadequate, inefficient homes. Across Europe, the latest data tells us that about a fifth of people cannot afford to keep their homes cool in summer. This makes for a precarious position when heatwaves occur, as is increasingly the case due to climate change. The poorest and most vulnerable are disproportionately at risk. Elderly and children’s bodies are more vulnerable to overheating. For socio-economic reasons, those with lower incomes, people of colour, and homeless people are also on the frontlines, as they tend to live in the most inadequate homes (or none at all) and have the least access to cooling.

We know heat also combines to amplify other environmental health risks – especially air pollution, which particularly affects the elderly, people with heart conditions and chronic disease, those working outside and children.

Strikingly, summer energy poverty receives little attention from media or politicians. Eurostat, the EU statistics agency, monitors numbers on winter energy poverty every year, but little data is available on summer energy poverty.

We know this heat is only going to get worse. Heatwaves could increase 50-fold by the start of the next century. A new study in the UK predicts that heat-related deaths are set to triple to 7,000 a year by 2050. Current global warming trends could mean three quarters of humanity face deadly heat by end of century.

For those who can afford it, installing air conditioning (AC) will keep them cool. But collectively, this promises only to further warm the planet, as it draws more demand for (fossil) energy. Global energy demand for air conditioners is set to overtake that of heating by 2060. In some cities, AC already accounts for 40 per cent of power usage. There are also immediate negative consequences: ACs tend to heat up urban areas, exposing people outside to even higher temperatures.

The way forward

What 2018’s heat has taught us is that we need both more far-reaching and urgent action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (mitigation), medium-term solutions to help society cope with living in a warmer world (adaptation), and immediate relief for the millions of Europeans already suffering from overwhelming heat.

We are heading for a 3°C to 5°C warmer world if we do not radically change our economic model. Current climate policies, including new EU renewables and efficiency targets, are far from adequate – and are being undermined by contradictory efforts to build new pipelines, airport runways, fracking rigs and to subsidise fossil fuels. To have a chance of a safe and cool climate future we need the strongest action now to get Europe fossil-free.

We also need adaptation plans for all of Europe, to prepare for hot (and stormy) years ahead. This heatwave has demonstrated we are far from ready. We need better urban planning, more planting of trees and better planning for city green spaces, better water management for our agriculture, more effective forest fire prevention and coherent heatwave plans.

Massive investments in fitting out insulated, energy-efficient homes has tremendous potential to both mitigate and adapt. It can help protect people during heatwaves (as well as freezing temperatures) – especially if it’s directed at the most vulnerable – and it reduces carbon emissions and allows for a switch to 100 per cent renewable energy.

And finally, we also need immediate steps for relief. In 2003, a record-breaking heat wave killed 70,000 people in Europe. We were not ready for the public health crisis then: hospitals were unprepared, special care for the elderly and needy not put in place, information was not disseminated. During heatwaves we need public awareness on health risks, hotlines providing advice, free public transport, cooling areas, water distribution in public spaces – and hospitals must be prepared. Will we be ready next time?