In Denmark, pig farming has rapidly intensified over the last decades, making it the country with the most pigs per capita worldwide. But how is it to live next to enormous pig factories? How does intensive pig production affect the Danish environment?

NOAH / Friends of the Earth Denmark visited local environmental groups all over the country to know more about their fight to close down large pig stables and raise awareness on the negative impacts of pig farming: air, water and soil pollution, heavy truck traffic brought onto the roads children use to go to school, bad animal welfare management – to name a few.

The costs of intensive farming

In the EU, 39% of total land is used for agricultural production. This share of land is largely shaped and controlled by the European Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) – a policy that supports farmers financially but also regulates food prices on the market. The CAP represents as much a third of the EU’s total budget and, as it stands today, encourages intensive farming, fierce competition on the international market and the expansion of existing farms.

Denmark is no exception: 60% of Danish land is used for agricultural purposes and benefits from EU subsidies – and therefore the Danish landscape is mainly characterised by huge monoculture fields and large pig stables. It is the most intensely farmed country in Europe. This is not without consequences for the surrounding nature, as agriculture intensification and expansion are the main drivers of biodiversity loss1. Occasionally, you might see a farmer in his tractor with a big machine attached, but beyond that the local environment is left with air full of spray poisons and slurry smells. There are rarely insects or other people in the fields. According to the European Environmental Agency (EEA), the state of the Danish biodiversity is amongst the worst in the EU, with the lowest levels of protected nature in the whole Union.

Denmark breeds 32 million pigs each year, a number that has been increasing steadily over the last years. For a small country of 5.8 million inhabitants, this equals to more than 5 pigs per person each year. But this intensive pork production is mainly intended for export rather than the local market and gravely impacts the environment, the climate and local communities.

Even though 80% of the Danish agricultural land is used to produce feed, it is still not enough to feed the whole livestock production. The industry is thus dependent on importing crops from abroad, such as soy. Today, Danish agriculture occupies an area in South America the equivalent of 31% of the Danish agricultural land1. Various studies have revealed how the deforestation of the Pantanal, Chaco and Amazon in South America is linked to the expansion of the agricultural sector, and besides cattle, production of soy for European livestock production is a main contributing factor. The communities living close to these industrial soy fields are the ones suffering the consequences: health issues and destroyed crops due to heavy spraying of the soy fields, water grabbing and even displacement.

Emmeline Werner from NOAH / Friends of the Earth Denmark emphasizes the devastating effects of the Danish pig production:

“Importing soy from abroad is clearly neither sustainable nor just from a human rights perspective. Denmark cannot continue with its large livestock production and claim to be a frontrunner in the green transition. The Danish pig production has severe consequences for local communities in Denmark and abroad. Without a decrease in meat and dairy production, Danish agriculture will continue to be responsible for environmental degradation and the increasing climate crisis.”

Denmark tries to makes the case of a “climate friendly meat”, claiming that Danish meat production emits about 220% less greenhouse gas compared to other European countries’. However, this claim has not been proven, and this argument is an illusion at best2.

Impact on local communities

Large factories of up to 100 000 pigs are not uncommon now in Denmark. This intensive livestock production has severe consequences for the environment and communities living next doors. Smell, air pollution, sound and heavy traffic on small village roads are part of their everyday life. Neighbors report various health issues such as headaches, nausea and lung problems due to the air pollution from the pig factories. A recent study from Holland confirms that there are severe health risks associated with living in the area around a pig factory.

In the 2019 Greenpeace documentary “Neighbour to a pig factory”, a neigbour reported that she could not walk outside without a face mask. Others are worried for their kids getting sick with lung infections every month. They campaign aginst the expansion of already large-scale pig factories but local governments have only little room for rejecting large pig farm owners’ applications to expand even more. In 2020, members of various communities decided to establish the national organization against pig factories (Landsforeningen mod Svinefabrikker).

The association organises around 600 people from local groups all over Denmark. They argue that due to the enormous size, noise and pollution of the pig farm factories, it should be classified as an industry and not agriculture, and therefore should be located in industrial zones, not around neighborhoods.

Birgitte Østergård Hansen, from Miljøforeningen på Tuse Næs, says:

“The large pig production facilities are no longer farms, they are industrial factories causing high levels of pollution, smell and noise. They should not be allowed to exist and expand next to areas where people live. In our association, we call these facilities by their appropriate name – pig factories.”

One central group of the national association is the Environmental Group in Tuse Næs, a village located close to the Isefjord and a protected Natura 2000 area. Tuse Næs was amongst the first communities to organise themselves and speak up publicly about the way factory pig farming affects nearby villages.

Birgitte Østergård and Finn, from the Environmental Group in Tuse Næs, told NOAH that the local “pig baron” owns four pig factories in Tuse Næs, in addition to the pig factories his family runs in other parts of Denmark and in Romania. He is willing to multiply on of his farm’s pig production by four despite its closeness to a Natura 2000 area and houses. On the formation of the environmental group, Birgitte explains:

“There were many neighbors who were worried about the size of the factories. And when we saw the plans to expand, we could see that our lives would be destroyed, if he got the permission. Now we worry that the municipality will suddenly approve an expansion.”

Organise and resist

In Jungshoved, a group of worried citizens also decided to organise and resist. The environmental group in Jungshoved (Jungshoved Miljøgruppe) started around 20 years ago as an organisation to protect the local environment, but is now focusing more on intensive pig production and its impact on groundwater through manure burnt in biogas plants and spread out on the fields.

Ilse Hein from Jungshoved Miljøgruppe says:

The waste fraction is mixed with the slurry and spread on the ground, where nobody knows the cocktail effect, nobody knows the impact on groundwater and surface water flowing into Natura 2000 and nobody knows the impact on biodiversity. The biogas plant has now become a power generating industrial enterprise, where the owner does not have to digest the manure, but just makes money on electricity production. Our land, air and water have become the industrial pilot site.

The pig factories split the villages and create conflicts between local communities, explains members from the Landsforeningen mod svinefabrikker. The owners of the factories are often big landlords, well implanted in local communities. They participate in social events, help people get their boats up from the sea with their tractor or give away half of a pig to their neighbors for Christmas. The environmental groups’ members deplore that speaking up can thus create many conflicts between people in the village.

Resisting the expansion of the big pig industry is resource-demanding, as it requires detailed knowledge of the legislation and municipality decisions in complex legal language. Therefore the local groups assist each other and share experiences on how to answer public hearings, or how to write official complaints on the government’ decisions. The local group in Tuse Næs also collaborates with the retired water engineer and activist Jan Henningsen to raise awareness about the topic. He has been documenting the environmental effects of intensive pig production for more than 30 years. He says:

My pictures get a lot of attention when I share them on social media. People are shocked to see how dead the life in the fjord is due to pollution.

The national organisation against pig factories has helped bring awareness to the topic on a national level. In 2020, the environmental minister Lea Wermelin promised to start an investigation of the health risks associated with living close to large pig factories. But since then, little has happened. However, local groups are still positive that a change can and will happen:

We see an increased awareness on how destructive the Danish agricultural model is for the local environment, water and the climate. Some years ago, few people talked about this, but now agriculture is a common topic in the climate debate. I am positive that we can make a change, but we need fundamental and big changes of the whole agricultural sector and targets to reduce livestock production if we are to achieve that. There is still a lot of work to do.

The CAP National Strategic Plans, an opportunity?

To change the pig production system in Denmark, local environmental groups argue that municipalities should start listening to local communities and stop authorising pig factories’ extension requests. Instead of giving in to agribusiness lobbies’ interests, the government can decide to allocate subsidies to support a fairer and greener way of producing pigs.

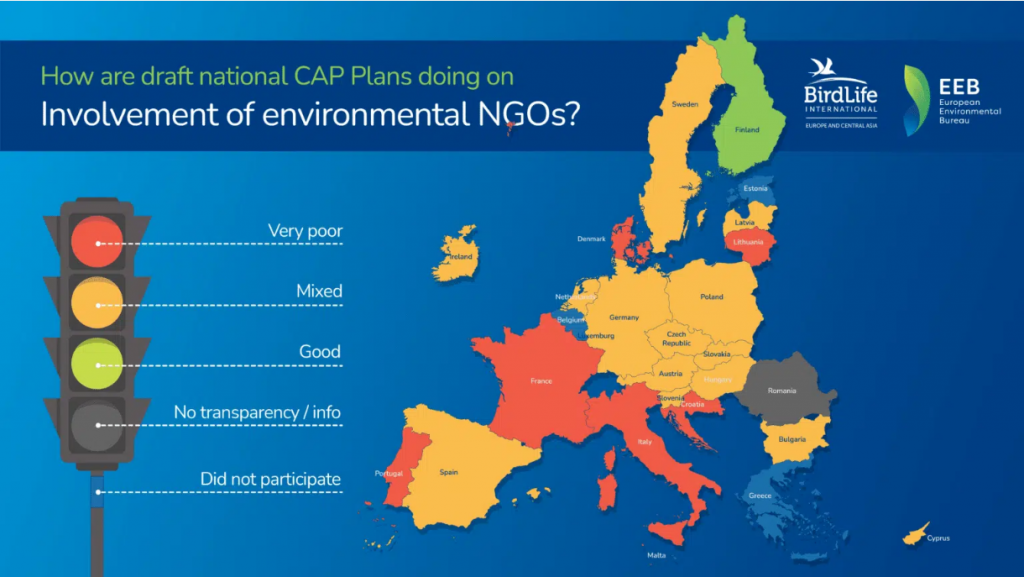

An recent assessment made by BirdLife and the European Environmental Bureau (EEB) in November 2021 analyzed the CAP National Strategic Plans’ drafts available at the time and screened them against seven key criteria stemming from the EEB’s 10 Tests for a Green Deal-compatible CAP. When it comes to the involvement of environmental NGOs for instance, Denmark scored very poorly. Have a look at the scorecards to see how countries score on each criterion.

According to NOAH / Friends of the Earth Denmark, there is little hope that with the new CAP, the changes needed will be supported. The new reform appears greener on paper, promises to increase organic farming areas or promote “crop diversification”, but nothing is mentioned regarding decreasing the livestock production. If something has to change, the EU Green Deal should be binding and force Denmark to convert their intensive agricultural model towards agroecological practices to improve health, the environment and the climate.

NOTES

1 Holmstrup, Schjelde, Lundsgaard, Nygaard, Ogstrup, L. and Iversen Damm, B. (2018) Sådan ligger landet – tal om landbruget 2017. Copenhagen: Danmarks Naturfredsforening og Dyrenes Beskyttelse https://www.dn.dk/om-os/publikationer/sadan-ligger-landet/

2 Lesschen et al. (2011) Greenhouse gas emission profiles of European livestock sectors, Animal Feed Science and Technology 166–167 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0377840111001775

Weiss & Leip (2012) Greenhouse gas emissions from the EU livestock sector: A life cycle assessment carried out with the CAPRI model, Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 149 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167880911004415

Wirsenius et al. (2020) Comparing the Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Dairy and Pork Systems Across Countries Using Land-Use Carbon Opportunity Costs, World Resources Institute Working Paper https://files.wri.org/s3fspublic/comparing-life-cycle-greenhouse-gas-emissions-dairy-pork-systems_0.pdf