Finland and Denmark have recently become the latest countries to adopt binding climate laws.

In June, measures were agreed in Copenhagen to move the country towards a low-emissions society by 2050, while the Finnish government committed to 80% CO2 reductions by 2050.

After years of work towards climate legislation in the two countries as part of Friends of the Earth’s Big Ask campaign the new laws look like causes for celebration, But whilst Maan Ystävät Ry/Friends of the Earth Finland is jubilant, NOAH/Friends of the Earth Denmark is disappointed. What is the explanation for this contrast?

Finnish ambition

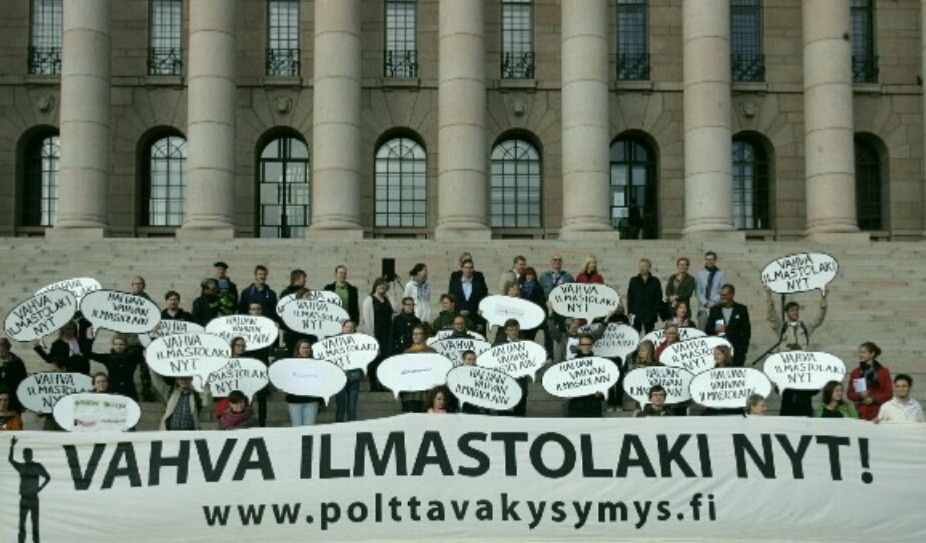

On 5th June, political parties across the board in the Finnish government approved the climate bill. The new law is set to come into force in the spring of 2015.

The bill commits Finland to 80% emissions reductions from 1990 levels by 2050. It includes the possibility for the revision of targets and plans according to the latest climate science, meaning that the target could well be increased.

The bill also contains a well-developed planning and monitoring system to ensure that steady progress is made along the way. The long-term plan would have to be approved at least once every ten years. A separate medium-term plan exists to address emissions outside the EU emissions trading scheme such as transport, housing and agriculture. This will have to be approved once every election term, and the government will have to report on it annually.

As the Finnish Minister of the Environment Ville Niinistö put it, “Through the Climate Change Act, Finland strives to be at the forefront of building a successful low-carbon society. The act merges ambitious climate policies with economic success and the improvement of well-being. Climate change and the efforts to mitigate it will change the world and human activities substantially in the coming decades.”

The announcement comes after long-term campaigning from Friends of the Earth Finland, who, through the Big Ask Finland campaign, put pressure on the Finnish government to “save them from climate catastrophe”

The process, however, is not yet over. In order to ensure that the bill remains up to the scale of the climate challenge, Maan Ystävät Ry/Friends of the Earth Finland is continuing to call for – amongst other measures – a 95% emissions reduction target for 2050.

Danish compromise

In contrast, the new Danish bill agreed on June 11th has been described as “rather thin” by NOAH/Friends of the Earth Denmark.

There is a stated intention in the bill of a transition towards a ‘low emission society’ by 2050. But the law is little more than one page long and does not introduce any new emissions reduction targets. This lack of concrete goals is described by Palle Bendsen of NOAH as being like, “a fish with a head and a tail and very little in between”.

New emissions targets are not identified (the existing national target of a 40% reduction of climate gases by 2020 remains), nor is a framework for emissions reductions in crucial sectors including energy, transport, agriculture, construction & infrastructure, waste and land use.

One outcome of the new law will be the creation of a permanent ‘climate council’. However, it remains to be seen what role this will play, given that the Environment Economic Council already exists, and the energy minister already has to give an annual climate and energy policy statement in the parliament.

Disappointment with the law is shared by Ellen Margrethe Basse, a professor of climate law at the University of Aarhus, who noted that, “If the law has an effect, it is the creation of a new climate council. This is really the main one, I think. Consequently, it should perhaps instead have been called the law on climate policy advice.”

What Palle Bendsen describes as the “patchwork character” of Danish climate legislation has been common knowledge for a number of years in Denmark, and NOAH/Friends of the Earth Denmark – along with Professor Basse – have pushed for a strong, binding climate law since 2008. Strong opposition from the Danish ministries of finance and justice resulted in the watered-down non-binding piece of legislation that exists today.

The Danish law is more surprising given that the Danish government already has some of the strongest climate targets and a track record on climate policy that puts it above the average in the EU. The government’s goal is to produce 100% of national electricity and heat from renewables by 2035. By 2050, the transport sector is also set to be free from fossil fuels, although offsetting is not excluded.

Whether successes or failures, these laws come at a crucial time for climate policy across Europe. A campaign for a climate law in Ireland continues with the government promising legislation by the end of the year. Meanwhile, EU countries are scheduled to agree a new package of climate and energy targets before the end of this year. The current proposal for 40% emissions cuts by 2030 is insufficient and dangerous, and the latest draft energy savings targets have been described as a “disgrace”.